When faced with another couple of tourists saying how welcoming and kind they found everyone in Belfast, our driver Danny said, “Well, yes, that’s it really. Belfast people are very kind to everyone. It’s just that it’s each other that they’re not kind to!”

We were taking a black cab tour of Belfast to see some of the Peace Walls or Peace Lines put up to separate the Catholic and Protestant communities during the Troubles, stopping off at some of the murals that mark infamous historic events.

This is sometimes called Dark Tourism, but we felt that we were informing ourselves one up from watching a TV documentary or feeding off memory alone. We were touring parts of Belfast the same day that President Clinton (and the remaining signatories to The Good Friday Agreement) were in town to mark its 20th anniversary, some coincidence. Our driver, Danny, did not just stay in the driver’s seat and give us a drive-by commentary. He often pulled over and climbed into the back, armed with newspaper cuttings, photos and the like, and helped us put what we were seeing into some sort of context. We started in Protestant areas of the city before visiting Catholic areas. Danny was brim-full of information and was passionate throughout. He may have been impartial but were we qualified to tell? “It’s no longer just about religion”, he said. “It’s about identity.” He was hoping that some of what he was imparting would be new to us because it never made it to the mainland in the media at the time. Please debate.

Murals

The murals are relatively well-known to mainland Brits, the stories behind them perhaps less so. We drove past or stopped at just a small proportion of Belfast’s total.

Up close and in the flesh, it was clear that these were markers of atrocities, of personal heroism and of cultural identity and defiance. To some, they will also be profoundly provocative.

The Women’s Quilt

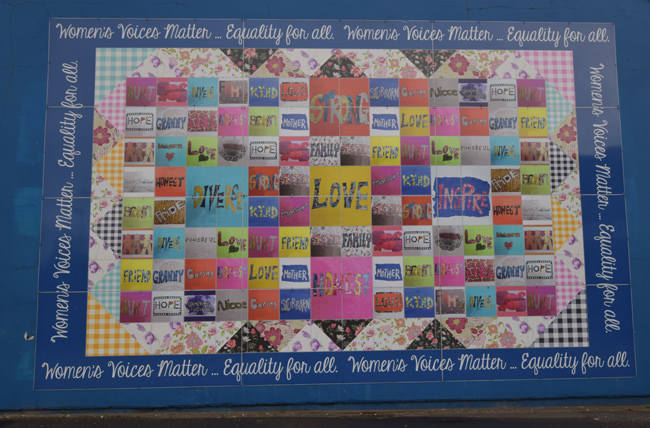

Dotted around the Shankill area of Belfast were these Women’s Quilt murals. I’ve reproduced below the full text that was displayed alongside one of them, as I couldn’t hope to improve upon these words myself.

“The Lower Shankill Women’s Group created this artwork using the theme of a traditional family quilt as their inspiration. The quilt idea was chosen as an item, which is often made together by family members and is ultimately handed down through the generations. The women decided to decorate their quilt with words that described themselves and their family members. Each member of the group contributed to the project, which were brought together digitally to form the overall artwork. They also wanted to highlight that women have a pivotal role within the Shankill area and that their voices are as important as anyone else’s.

“Artist Lesley Cherry worked with the women during this project, drawing out family stories of care, loss, remembrance and ultimately love, not only for their immediate families, but for their friends and the wider community.

“This artwork was funded by the Housing Executive, working in partnership with the Lower Shankill Community Association. The artwork replaces a contentious paramilitary mural and an artwork depicting the burning of Protestant homes at the beginning of the Troubles.”

The Peace Walls

If many of Belfast’s murals are markers in historic ground, milestones hammered into the unfolding narrative of past troubles, the Peace Walls are something entirely different, functioning as barriers to separate tribe from tribe, neighbour from neighbour, not just in the past but also in the present of today. This was new to us.

There are nearly 60 miles of these barriers in Northern Ireland, most in Belfast, stretching over 20 miles in length. There are walls of brick or breeze block, walls with fences on top, fences faced with steel sheets and then fences topped with even more fencing, climbing upwards as the lobbing height of offense increased. In places these rise to nearly 8 metres. Some run along open ground, others alongside roads. A few back up against the ends of back gardens and yards, whole estates in length. The names Falls Road and Shankill Road have been familiar to us for years, notoriously so. Where these barriers intersect entry points to a different community, there are steel gates, open during the day, sometimes manned by police, sometimes closed and locked at night. That we did not know.

Some of the barriers are unadorned, functional. Others serve as canvas for graffiti. Others have become surfaces for votive offerings, scribbled prayers, exhortations to peace. Others are emblazoned with propaganda or artistic statements of solidarity with other struggles against oppression internationally. Take your pick which viewpoint you occupy. As the phrase has it, one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter.

Below is a stitched panorama of part of the Protestant side of the Cupar Way peace line, north of the Falls Road.

(click for a larger version: 850Kb file size, 2,100 pixels wide)

And another, much wider, stitched panorama of part of the Catholic side of the Northumberland Street peace line, just north of the Falls Road.

(click for a very large version: 2Mb file size, 9,900 pixels wide)

Beside the Catholic Clonard Martyrs Memorial Garden, where the barrier running along Cupar Way backs on to Catholic houses, some of these houses are equipped with protective cages to reduce the damage that anything lobbed or fired over the high fence might do. I’m not sure I would have believed this without having seen it for myself.

Relatively recent surveys have shown that a majority of Belfast’s population want these barriers to stay up. There is an inter-communal plan to dismantle all these peace lines by 2023. Whether the uncertainties surrounding Brexit will in fact derail that plan remains to be seen. Are these identity issues properly understood in Westminster?

Links

- The Peace Wall Web Archive: http://www.peacewall-archive.net.

- The Talking Stones website: http://northernirelandmemorials.com.

- Life in Belfast as represented on its walls – murals, graffiti, street art: Extramural Activity.

- CAIN, Conflict Archive on the INternet: http://cain.ulst.ac.uk.

- Paddy Campbell’s Famous Black Cab Tours: http://www.belfastblackcabtours.co.uk. Or ask for Danny by telephoning 0789 994 5925.

- Michael Savage, In Belfast fear is growing that the hated barriers will go up again, The Guardian, 6th May 2018.

- Lisa O’Carroll, Rees-Mogg: I need not visit Northern Ireland to understand Brexit issue, The Guardian, 11th May 2018.