A painting by Robert Tait in the front parlour of 24 Cheyne Row dated 1857 shows Thomas and Jane Carlyle in their front parlour - at 24 Cheyne Row. Looking at it is like looking through a window into the room in which one is already standing. But the original occupants are there, in painted repose, as we modern-day intruders peer in through a looking glass and step through their ghosts. Thomas Carlyle, leaning on the room’s marble mantel piece, is priming a clay pipe. Jane Carlyle, settled beside a lit fire, is gazing across the room at her terrier Nero. The painted chair in which she sits is still there today (albeit re-upholstered) as is nearly everything else in the painting - save the married couple and their dog. The National Trust has done a fine job in preserving the place and making it something of a shrine to the Carlyles, a haven of retro-calm and relative normality in Chelsea of all places.

One could easily be deceived. True, Carlyle (1795 - 1881) is greatly respected for his 1837 History of the French Revolution, the first volume of which was accidentally destroyed when John Stuart Mill’s servant mistakenly threw the manuscript on the fire, and which Carlyle subsequently re-wrote. True too that, as the 2013 edition of the National Trust booklet on the property has it, that Carlyle was “an immensely influential social commentator and historian who shaped the way the Victorians thought about themselves”. The booklet continues: “He believed that the Victorian pursuit of money and naked self-interest was corrupting human relationships”, which makes 24 Cheyne Row’s presence in the bosom of Porsche and Bentley-filled Chelsea all the more poignant.

What appears buried - at least until the National Trust booklet enjoys a reprint - is that Carlyle had some repugnant views on race and slavery. His 1849 Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question suggested that slavery should never have been abolished (as it was in the British Empire by 1833), and that it would have been better for it to have been replaced with serfdom or indentured servitude. (Does Carlyle’s view that the supposed financial ‘security’ offered by these systems was preferable to impecunious ‘liberty’ in any way diminish the broader controversy?) Either way, Carlyle believed that slavery had kept order amongst those who “refused to work”. Carlyle’s Wikipedia page elaborates on this - as does the explosive essay in question (links below), all of which is worth bearing in mind if you visit the delightful 24 Cheyne Row.

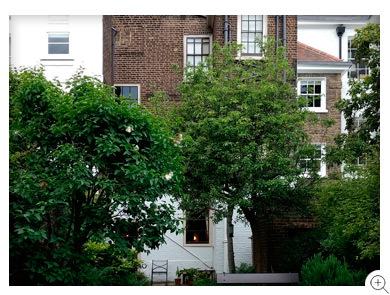

(Photographs of the interior of the house to be added once the house re-opens.)

Links