Rathlin Island is Northern Ireland’s only inhabited offshore island. It lies 15 miles from Scotland’s Kintyre Peninsula and is a 6 mile ferry hop from Northern Ireland’s Ballycastle. It may be just 45 minutes on the water but, not unlike Seamus Heaney’s father, it comes into view twenty or even fifty years away. The allure of islands continues to pull on Rathlin as it does on many a small island, pulling you back to a time when the pace of change may almost have been unnoticeable.

A make-do and mend approach to life re-cycles everything, whether boat or croft, almost beyond its usefulness at which point, bleached and fragmenting, it is abandoned, scavenged or left to rot. Man’s influence on the landscape seems to pass in time-lapse frames, one generation after another, folding back onto the rock, perpetually worn away by tide and storm. A fresh lick of paint and a welcoming smile do much to dispel this, but a gnarled hardiness must have planted the island’s residents to the place or shaved them off singly to chase opportunity elsewhere.

Site of neolithic axe heads, target of Viking raids, refuge for Robert the Bruce and grim scene of bloody English massacres, Rathlin has history. Unlike in parts of urban UK, time never obliterates the history of small islands. So a high premium is placed on the bonds of community and on good humour. Historic flight to opportunity elsewhere have now become a trickle of escapists in the other direction. What was once an ageing island population is becoming an increasingly younger one enjoying a steady renaissance thanks to returnees and newcomers alike. The allure of islands abides.

The Rathlin Island West Light

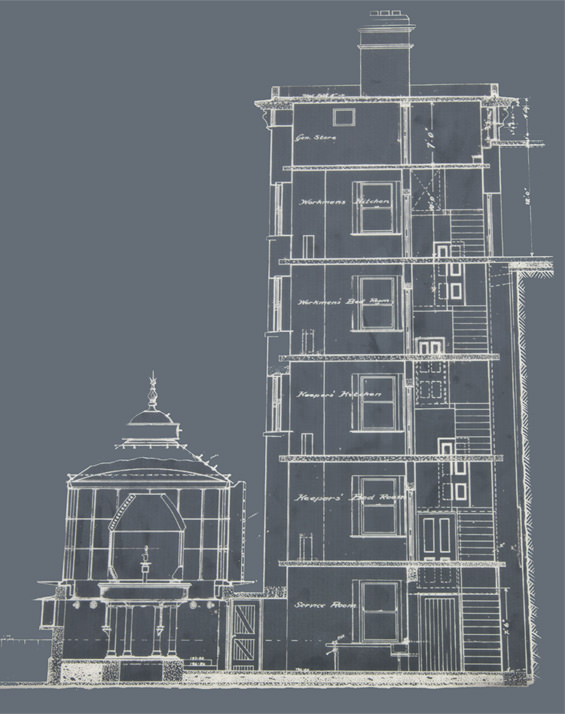

It’s easy to see why Rathlin’s West Light is included in the group known as the Great Lighthouses of Ireland. It is perched a third of the way down the sheer cliffs at Rathlin’s Atlantic-facing edge, warning approaching shipping of potential calamity. The rip tides and currents that swirl between Rathlin and Scotland’s Mull of Kintyre catch out even the most seasoned sailor. Planting a light here that can push a pencil beam of light out just over the horizon’s falling curve, and topping it with a foghorn - that came to be known as the Rathlin Bull, which could be heard 30 kilometres away - would have been a compelling decision.

The upper part of the cliff at this point needed stabilising and encasing. So between 1912 and 1918 an estimated seven million kilograms of concrete were hauled up these cliffs - without loss of life - and then mixed by hand with shovels. This heavy-lift necessitated some form of mechanical assistance and to that end an inclined rail was fixed in place with a small jetty and crane at its foot. With a winch house at the top, a single horse could strain away and haul up small purpose-built trucks containing an endless supply of materials that had been landed by tender boat below.

The completed lighthouse is accessible by steps from above and is therefore distinctively an upside-down lighthouse with its light planted at the base of the tower in which the keeper lived. Today there is no access to the light from the water below.

This unusual accessibility to the Rathlin West Light made the keeper part of the island community, not some isolated hermit. Because keepers needed to keep detailed logs, they needed to be literate. This gave them some degree of status within the community at a time when literacy was not commonplace. It was not unheard of for islanders to trust the keeper enough to ask for help with reading and writing letters.

Rathlin’s West Light was automated in 1983 after an unbroken run since 1919. It is now open to the public - and not just because the RSPB Bird Reserve’s viewing platform can only be accessed by walking through the lighthouse. Various parts of the building have been arranged as a mini-museum with excellent information panels explaining aspects of a keeper’s job.

The Rathlin Island West Light RSPB Reserve

Open from March to September, the Rathlin Island reserve gives vertiginous views onto important colonies of breeding puffin (conservation status: red), kittiwake (conservation status: red), razorbill (conservation status: amber), fulmar (conservation status: amber) and guillemot (conservation status: amber).

Our arrival at the reserve on 8th April coincided to the day with the return to the cliffs of the puffins in their glorious summer plumage. They had started coming back to their familiar breeding cliffs from their winter-feeding grounds in the north Atlantic or Bay of Biscay, each bird repeating a solo journey around their individual feeding-grounds winter after winter. Ninety-five percent of the adults here last year will be coming back this year, barring wide-spread disaster. In Adam Nicolson’s exquisite phrase, these birds are the oscillating nomad-masters of an unpacific ocean.

As I write this post in April 2018 BirdLife International has published its latest five-year compendium of bird population data, putting the Atlantic puffin for the first time on its Red List of imperilled and vulnerable species. (Over-fishing and climate change are considered to be the factors responsible for their decline.)

The reserve’s sea stacks are what draw the birds in (as no eggs can be laid on the Atlantic’s water) and they occupied the high-rise accommodation of these stacks in horizontal bands. The guillemots took the heights, and the upper shelves, with no more than seven square inches of rock for each individual - maybe 50 occupied sites for each square yard - pressed up against at least eight neighbours in dense carpets or, on narrow ledges, crammed into precarious strings of perpetual side-by-side jostling. Below them were the kittiwakes and fulmars, dotted about in couples wherever a nest could be scraped or flattened into sufficient horizontal space for them and their eggs. Near the bottom of the cake, puffins were cleaning themselves, not yet re-adopting last year’s burrows. On the rocks below them, tucked into crevices, were the razorbills in their monogamous pairs.

We saw the Rathlin West reserve just as the birds had started to return for the breeding season. It was probably too early in the season for eggs and certainly for chicks. Even so this was a dizzying experience. The ability to lean on sturdy rails and look down into a sweeping abyss and across to an axe-head-shaped stack beginning to be populated by seabirds was indeed very special. Hats off to the resident wardens and seasonal volunteers who keep the place in such great shape!

These ocean-going creatures prompt a form of meditation about their resilience and yet their frailty in the face of mankind’s destructive power. For years the West Light, perched guillemot-like on its own shelf, has served as sentinel against ship-wreck. The adjacent reserve has had an unequal pull in the opposite direction on innumerable seabirds for time immemorial. See it whilst you can!

Links

- The Great Lighthouses of Ireland: http://www.greatlighthouses.com.

- The Irish hare: http://www.habitas.org.uk/priority/species.asp?item=42516.

- The RSPB’s Rathlin Island page: https://www.rspb.org.uk/reserves-and-events/reserves-a-z/rathlin-island.

- The commendable Rathlin Community website (Drupal, yay!): http://www.rathlincommunity.org.

- The International Union for Conservation of Nature, the IUCN Red List: https://www.iucn.org/resources/conservation-tools/iucn-red-list-threaten….

References

- Adam Nicolson, The Seabird’s Cry, the lives and loves of puffins, gannets and other ocean voyagers; William Collins, 2017, ISBN 978-0-00-816569-7.