Chastleton House in Oxfordshire is a compact Jacobean gem of faded surfaces, bumps and blemishes. Since the early 1600s, its occupants aspired to a status above county gentry but habitually fell short. As Royalists or Jacobites, whose fortunes waxed but mostly waned, their inability to prevent the house’s progressive disrepair saved it from all manner of likely excesses.

Tucked in a fold of Cotswold countryside, it is a house of no real pretensions which the National Trust somewhat boldly decided to make safe and preserve - but not restore. Walk round it today and enjoy the wobbly plaster and blotchy paintwork and gain a brief sensation that you have entered a time capsule. With its own dairy, stables, brewhouse and bakery and the 12th century village church a few steps away across the forecourt, you could almost imagine that occupants of this quietly fading place were self-sufficient and never needed venture further than its elegant archway.

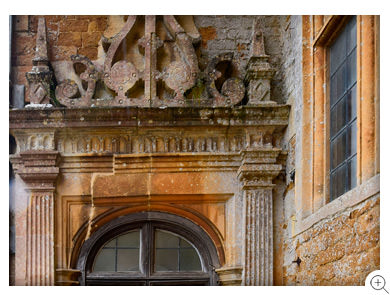

The south-east facing front rises three floors over a basement and is topped by five gables. Two of these are bays stepped forward to shelter the entrance, unobtrusively tucked to the left of a flight of steps, opening sideways into the porch (something one sees on an ampler scale at Broughton Castle, this site). Two massive staircase towers rise at either end of the building. The one on the west is for family and servants, that on the east is highly decorated and leads to the house’s Great Chamber. Compact finials on the roofline’s silhouette engage in a call and response with those on the stone archway. There are more inside. They are one of Chastleton’s hallmarks.

The south-east facing forecourt of Chastleton House - with the parish church of St Mary the Virgin adjacent

Detail of Chastleton’s Great Hall, showing the original screen and the oak table (dating from at least 1633) which was made in situ.

Detail of Chastleton’s Great Hall. A 1614 painting of Chastleton’s builder Walter Jones hangs above the fireplace and a 1605 painting of his wife, Elinor Pope hangs in the alcove to the left.

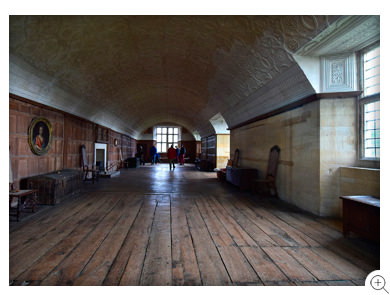

Chastleton’s breath-taking Long Gallery, the longest surviving barrel-vaulted ceiling of its period in England

The original 72-rung ladder for accessing Chastleton’s gutters, useful only if there is enough man-power to get it outside and erected.