Unexposed photographic paper is akin to John Locke’s tabula rasa. Translated from the Latin, the surface was a ‘clean slate’, a uniform grey, ready to receive the white chalk marks of thought and experience. He qualified this by saying that at birth the mind is a “white paper, void of all characters, without ideas”. So too in the photographer’s darkroom, the unexposed photographic paper is an unblemished white surface. Only when light passes through the negative is any sort of image gradually exposed, feint greys turning towards black in a positive representation of what the photographer first saw.

This process of film exposure in the camera, all the way through to photographic paper’s exposure in the dark room - the two controlled by the same discerning eye - is best seen in the work of master photographer John Blakemore, whose Seduced by Light exhibition at the Centre for British Photography I was lucky to catch this September.

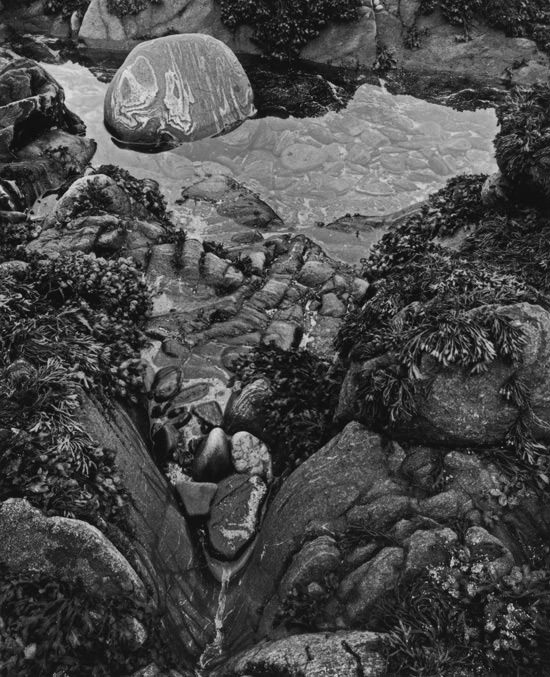

As we view these images, there is some preliminary ‘positioning’ that is required. The first relates to black and white photography which removes the distraction of colour, and invites us to linger over form and tone. As we see in colour, a monochrome image stimulates us to view it from a different perspective. These images do not ask us to consider veracity or verisimilitude. Instead, they ask us to stand beside ourselves and view an artefact, a distillation. These are paintings made with light.

There is then the issue of medium. Blakemore’s images were initially physical prints. They appeared in exhibitions, were published in books and, towards the end of his hugely productive career, were entrusted to hand-made booklets, objects of intimate beauty. In these variations, the tangible medium of printed image dominates, sometimes with the feint grain of fibre-base photographic paper being part of the viewing experience. Each image has been developed by the photographer, birthed in the darkroom. The transfer of shade and tonality involved has a continuity, an authenticity that connects the moment of exposure in camera with what the resulting print image conveys. We view images created in the digital age as if they project light from a source behind them. Blakemore’s analogue images require light to play on them from gallery lighting.

We might also bear in mind that today’s image manipulation (think Photoshop) had some equivalents in the darkroom. Exposure could be held back with ‘dodging’ and accelerated with ‘burning’. Choice of film paper, timing and cropping served just as much to influence the final result as today’s post-processing. Indeed, everything about Blakemore’s exquisite photographs is as removed from representation as one can get, and this is very much the point.

Blakemore’s career has been long and illustrious, commencing with a reportage style of photojournalism in Tripoli during active service, followed by a period of producing gritty community portraits in the Midlands. A series of landscape and nature photography was then followed by a retreat to his home studio, both phases engaging experimental studies. In parallel with this, Blakemore taught photography at Derby College of Art/the University of Derby, where he became Emeritus Professor of Photography. This post is concerned only with the landscape and studio photography.

One tends not to expect much by way of narrative or explanation from an essentially visual artist, yet find that Blakemore is an exception in this. That he also taught photography suggests as much. “I enjoy language”, he wrote, “and am an avid reader”. Much of his written commentary can therefore be trusted as bearing reliable witness to his own work.

The beach photograph at the top of this page and the rock pool one above, appeared as Blakemore found landscape to be a release, “a return to the pleasures and pursuits of my childhood which had been lost to me”. “Exploring landscape,” he wrote, was as “a manifestation of energy”. In these close-up studies, he built “a ritual of intimacy, around the sustained exploration of small areas”. The rock pool of 1976 was taken in Scotland “on a day of soft light”. The “gestural markings” of the domed rock attracted Blakemore, as much as “the weed-draped rocks and the triangular geometry of the rock pool”. For the 1979 beach shot, Blakemore used test strips of varying exposure lengths to establish the desired contrast and tonality. Low, late-afternoon sun on the coast of North Wales required a multiple exposure technique to capture the stillness of the foreground with the moving waters beyond.

A further sequence moved from water to wind. Whereas the latter “is constrained and shaped by the landscape,” he wrote, it in turn “erodes and shapes the landscape that it moves through”. While wind also shapes the landscape, “its movement is impeded, and is moulded by the landscape it traverses”.

“To photograph wind is of course impossible; the photograph represents surface detail and the wind is invisible. But one can photograph its traces,” he wrote. Finding wind to be intermittent, Blakemore needed to find a way of capturing its “inconstancy”. The familiar technique of multiple exposures was the solution: by calculating exposure and dividing it into increments, he was able to make a series of exposures with a large-format camera. The light tonality, combined with short exposures, replaces detail with an emotional response to the scene. The camera, he found, “moved between fact and fiction”.

In 1981, Blakemore’s excursions into landscape were exchanged for a rootedness in the studio. If one of the hallmarks of his work is how he exerts control over the whole process - from photograph to print, then the removal of that which proved hardest to control - wind and weather - was a way forward. Thus began a period of extraordinary productivity, the results of which greatly burnished the photographer’s reputation.

His monograph The Stilled Gaze and Chapter Two of his John Blakemore’s Black and White Photography Workshop contain image after image of tulips, the former some 80 pages of them, the latter some 39. What began as an experimental sequence of still life photographs, occasioned by “an accident of season” - there being a bowl of tulips on his kitchen table - expanded into a nine-year homage to the flower. They have “gestural elegance,” he wrote. They “change through time: buds open, flowers ripen, stems straighten or curve, petals shrivel and eventually fall”. All these stages provide “new and often unforeseen picture-making possibilities”.

Initially, Blakemore concentrated on flowers in a bowl or a vase. Soft light illuminates the table on which they stand. A chair with an arched back rail echoes a tulip stem that extends towards it. Glimpses of pictures on a nearby wall give scale to the scene. At other times, a cat is party to this intimacy. These photographs depict unsurprising domestic scenes, save that their composition and tonality are clearly studied, contemplative. Light, shadow, reflection, glass, water, petal, stem and bouquet offer themselves to the lens with minimal artifice. Their unforced essentials are being explored. As the sequence progresses, the still lives being captured are more consciously being arranged and choreographed. Single flowers have been laid on a black or wooden background. A dozen of them conspire, confer, congregate, their plastic flesh caught timelessly beyond the reach of decay.

This gradual progression from the merely botanical to the sensual seemed to be evoking seventeenth century Dutch ‘tulipomania’ when fortunes were won and lost by bulb collectors. The contemplation of single flowers as seen in the paintings of Jacob Marrel (1614 - 1688) or of bouquets as painted by Bosschaert, Walscapelle, van Huysum and Ruysch had become, in Blakemore’s studio, a composition fit for a “tulip fanatic’s cluttered space”, captured in a 4-minute exposure illuminated with torch light, a rare exception to his comment that “I work exclusively with daylight”. It is the image appearing on the front jacket of Blakemore’s Photographs 1955 - 2010:

This is as complex as any landscape, far removed from the quiet simplicity of a bowl of flowers caught on a table. And it is to this that Blakemore was to subsequently return. “The quality of familiarity has always been significant to me,” he wrote. “I have always distrusted the penchant of photographers to seek out the strange, the unfamiliar, the picturesque.” What emerged therefore was a series of images taken in “a domestic space, a familiar space”. In these smaller scenes, what mattered was “the geometry of the space produced by the meeting points of objects”.

These simpler 35mm images contain all the elements that made his previous work so successful. They are painterly, the subject being not just the flowers “but all that the frame of the camera includes”. Light at an oblique angle on a flower casts a shadow in the shape of a butterfly, so Blakemore’s tulip remained a flower “of constant metamorphosis; it stretches towards the light and gestures to occupy the space”.

There is a career progression that has oscillated between complexity and simplicity, a progression that has resulted in subjects where less has become more, where the less detail there is in the subject for the eye to look at, the more there is for it to see.

Sadly, much of Blakemore’s published ouput is out of print. In our hastening world, these images have durability. Reprints of his major work would be most welcome.

References

- John Blakemore’s Black and White Photography Workshop by John Blakemore; David & Charles, 2005.

- Photographs 1955 - 2010 by John Blakemore; Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2011.

- John Blakemore, Seduced by Light, The Centre for British Photography (8th June - 24 September 2023).

Postscript

Even more sadly, John Blakemore died in January 2025. R.I.P.