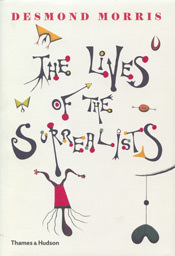

Desmond Morris is better known for his book The Naked Ape, which he wrote in 1967 (and which ranks amongst the top 100 bestsellers of all time), than he is for his surrealist paintings. Both of these amply qualify him for writing about some of the major players in the Surrealist Movement of the 20th century in his The Lives of the Surrealists, Thames & Hudson 2018. The Naked Ape: A Zoologist’s Study of the Human Animal presented his dispassionate view of the human species and was followed by The Human Zoo and a stream of work looking at human and animal behaviour. He was a fixture on British TV in the 50s, 60s and 70s, presenting the best part of 700 programmes and giving over 400 interviews.

The surprise to many is that Morris was also an accomplished artist who mingled with the surrealists and even shared his first London exhibition in February 1950 with no less an artist than Joan Miró. He personally knew eight of the artists he writes about. This is therefore an insider’s guide to the lives of some of the most prominent surrealists, written by an eminent zoologist. Given that many of these artists were exotic, sometimes plumed and preening strutters on the international art world’s stage, the match between guide and subject matter couldn’t be better.

The format is simple: one short chapter per artist, including for each a full page monochrome photograph and a full page colour reproduction of a representative painting or sculpture. Each chapter begins with the basic facts: nationality, birth, parents, places lived, partners and death, the biographic outlines. Flip through the book and scan read these in one go and the first impression you have is that the surrealists were rarely monogamous. That becomes a theme of the book, saying volumes about the stability or ego of many of these individuals. There were notable exceptions such as Alexander Calder, Joan Miró, Henry Moore and, surprisingly, Salvador Dalí, but the trend towards bed-hopping appears relevant.

Morris begins by grouping his subjects according to the strength of their membership to the surrealist movement. Each was either an official surrealist or a temporary, independent, antagonistic, expelled, departed, rejected or natural surrealist. Most bounced or drifted in and out of more than one of the categories depending upon the vicissitudes of the time. The author omits official surrealist non-artists and surrealist photographers and film-makers. There’s a chapter each on Eileen Agar, Hans Arp, Francis Bacon, Hans Bellmer, Victor Brauner, André Breton, Alexander Calder, Leonora Carrington, Giorgio De Chriroco, Salvador Dalí, Paul Delvaux, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Leonor Fini, Wilhelm Freddie, Alberto Giacometti, Arshile Gorky, Wilfredo Lam, Conroy Maddox, René Magritte, André Masson, Roberto Matta, E.L.T. Messens, Joan Miró, Henry Moore, Meret Oppenheim, Wolfgang Paalen, Roland Penrose, Pablo Picasso, Man Ray, Yves Tanguy and Dorothea Tanning.

It helped enormously to read this volume with a browser open on a nearby screen. Calling up examples of each artist’s work as their chapter came up grounded the experience. In some cases, I knew the artist’s work well enough. In others, the experience was novel. In embracing the lives of these artists with an appraisal of their art, Morris has provided valuable insight. The following is a nice example:

Miró was wildly abandoned in front of his easel, but calmly controlled in his private life. Tanguy was calmly controlled in front of his easel, but wildly abandoned in his private life.

I found it revealing that so many of these artists came from privileged backgrounds. Picasso’s father was an art professor, his mother a minor aristocrat (no doubt giving rise to the artist’s 19-word string of christian names). Penrose’s mother was the daughter of a wealthy banker. Dalí and Delvaux had fathers who were lawyers. Carrington’s father was a textile magnate. Brauner’s father was a timber manufacturer. Agar’s Scottish businessman father had a town mansion in Belgrave Square. She herself had one suitor who was an English lord and another a Russian prince. That so many were in open rebellion against their strict childhood upbringing and veered towards the rebellious nature of surrealism was not perhaps surprising. What gave this real poignancy was the fact that many of the above came under the spell of surrealism’s leading light, André Breton, whose less-august parents were a policeman and a seamstress. That Breton so dominated most - but not all - of the above artists was fascinating, particularly as he was, in Morris’ words “a pompous bore, a ruthless dictator, a confirmed sexist, an extreme homophobe and a devious hypocrite”.

The surrealist movement had its roots in the avant-garde Dada art movement that rejected logic and reason, favouring irrationality. Surrealism was an attempt to codify these urges as starting directly from the unconscious mind, with absolutely no rational, moral or aesthetic censorship. Breton was the one to shape the movement in his 1924 Manifeste du surréalisme and became its self-styled leader, elaborating the movement’s rules and ensuring that they were obeyed. The inherent contradiction in asking your followers to let their minds run free by ignoring rules and regulations, whilst imposing on them a rigid set of rules which they were required to obey were the seeds of the movement’s eventual destruction and led to there being explosive resignations and expulsions. Morris’ volume sheds light on the personal dynamics that lay behind one of the 20th century’s most influential art movements. The book is even-handed and provides rounded profiles of complex individuals. Penrose’s generosity, Moore’s toughness and tenderness, and the intensely practical Calder’s integrity all shine out.

This is a valuable addition to the history of 20th century art by one of the last surviving surrealists.

References

- The History of Surrealism, Maurice Nadeau; Jonathan Cape, 1968.

- The Surrealist Movement in England, Paul C. Ray; Cornell University Press, 1971.

- Literary Origins of Surrealism, Anna Balakian; University of London Press, 1967.

- Surrealism, Patrick Waldberg; Thames & Hudson, 1965.

- A Concise History of Modern Painting, Herbert Read; Thames & Hudson, 1959.